Out and about with...

Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter, Operation managers High Alpine Research Station Jungfraujoch

Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter live and work at an altitude of almost 3,500 metres above sea level. They are the caretakers of the high alpine research station on the Jungfraujoch.

A Wednesday morning in July. At 7.30 a.m. we are already on the Jungfrau railway from the Eiger Glacier to the Jungfraujoch - Top of Europe. Without any tourists. In the so-called staff connection. From the chef in the Crystal restaurant to the service staff in the Eigergletscher restaurant. From the employee in the souvenir shop to the craftsman. They can all be found here, doing their daily work in one form or another at 3454 metres above sea level. Almost all of them. Because Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter don't have to commute every day. The maintenance staff at the High Alpine Research Station not only work on the Jungfraujoch, they also live surrounded by eternal snow and ice.

Researchers from home and abroad

When we arrive at the highest railway station in Europe, Sonja Stöckli is already waiting for us. We walk through a tunnel. Soon there will be numerous tourists from all over the world here. Then we turn right. "No public access" is written on a sign on the door. This is the entrance to the High Alpine Research Station. This is also where we meet Thomas Furter, Sonja Stöckli's partner. There is coffee - and water - in the lounge. "Drink plenty," Sonja Stöckli advises us. "The altitude is not to be sneezed at." The 56-year-old speaks from experience. Hundreds of researchers from home and abroad have already visited here. Welcoming and looking after them is part of her job as operations manager. "When we have overnight guests, I prepare the rooms," she says. She manages nine single rooms and one triple room in the five-storey building. But Sonja Stöckli also does a lot of administrative work. In other words, she is an accountant, receptionist, cleaner and telephone operator all in one. And a meteorologist - but more on that later.

From time out to dream job

"Being a little crazy" is what Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter write on their own little website in the "About us" section. That describes their last few years quite well. She, a qualified nurse, and he, a qualified electrical engineer, wanted to "get out of the hamster wheel". In 2020, they took a longer break. In five months, they will hike from Switzerland to northern Albania. A year later, they will walk from Greece through the Balkans. And then, back in Switzerland, they come across a job advert for the research station on the Jungfraujoch. They were looking for an over-50s couple with a good command of English. "A willingness to attend a one-day course for rope work, a two- to four-day forklift driving course - depending on previous knowledge - and a two-day meteorological course were also required," we learn from Thomas Furter. Around 50 couples apply and Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter are awarded the contract. Their first day at work on the Jungfraujoch is 1 June 2022. After a week of familiarisation, they are on their own. At least almost. They share the job of operations manager with another couple. They take turns every 15 to 18 days. Once a year, each couple takes a longer break of three weeks. At the "shift change" after just over two weeks, they briefly exchange ideas, "and the staff at the HFSJG (International Foundation High Altitude Research Stations Jungfraujoch & Gornergrat; editor's note) at the University of Bern also support us," we learn from the couple.

Shovelling snow - even in summer

Thomas Furter is responsible for the research projects, technical maintenance and infrastructure. His work often starts at 6 a.m. - shovelling snow on the Sphinx. "One and a half metres of fresh snow - that can happen in winter," says the 55-year-old. And yes, it also snows in summer at almost 3,500 metres above sea level. "Unfortunately not as often as it used to. Due to global warming, the precipitation often comes down in the form of rain in summer." The canopy of her flat in the research station also has to be cleared of snow regularly - secured with a rope. Not today. It's generally quiet on this Wednesday morning. "There are days when we work 12 hours. But there are also days when I have time to read a book in comfort," says Sonja Stöckli. But back to work. Two to three times a week, they guide groups of visitors through the research station and the Sphinx in German and English. Today we are enjoying one of these exclusive tours. Climbing stairs is the order of the day, quite strenuous at this height. I have to shift down a gear. Our destination is the fourth floor, the library. There are - of course - lots of books here. And records of research dating back to the 19th century.

Almost 100 years old

Yes, the history of the research station goes back to the 19th century - and is closely linked to the construction of the Jungfrau railways. When Adolf Guyer-Zeller received authorisation for the construction, which began in 1896, he promised in the concession to enable scientific research at high altitude. In 1912, nine years later than planned, the railway was completed. And from this point onwards, researchers began to benefit from the opportunities offered by this exceptional location. Discussions about the construction of a research station soon began. This became a reality in 1931.

The focus of research has changed over the past decades. In the beginning, the focus was on astronomy and radiation research, with physiological projects also taking place. Today, the focus is on environmental and climate research.

From radioactive measurements and liquid nitrogen

We follow Thomas Furter wherever he goes. With all these corridors, stairs, doors and tunnels, we would otherwise get lost pretty quickly. He shows us one of the five laboratories. Here he takes radioactivity samples manually. Two radioactive isotopes (carbon 14Cand the noble gas krypton 85Kr) have been measured for decades using two simple measuring set-ups. These measurements are used to monitor the atmosphere. Right next door, he produces liquid nitrogen. This involves liquefying nitrogen from the air to -196°C using a system from the 1960s. The liquid nitrogen is needed for two experiments, including the extraction of radioactive krypton 85Krisotopes. We listen to his explanations with rapt attention.

View equals zero

Thomas Furter looks at his watch. "Time for the 'Wättere'," he says. That's what the maintenance staff call the weather observations they carry out five times a day for MeteoSwiss. We pick up Sonja Stöckli, who is busy washing bed linen. From the research station, we make our way to the Sphinx. The tunnels are now full of tourists. We take the old lift up to the observatory to avoid the hustle and bustle. As much as I was looking forward to the view from this exclusive location on the roof of the Sphinx, which is not accessible to tourists, I am now disappointed. Fog. Visibility is zero. In less than a minute, the weather observation is over, it is entered in the tablet. "In good weather, you can see for 120 kilometres, and in clear and dry conditions in winter, you can even see for 170 kilometres, as far as Alsace," says Thomas Furter. Little consolation for me at the moment.

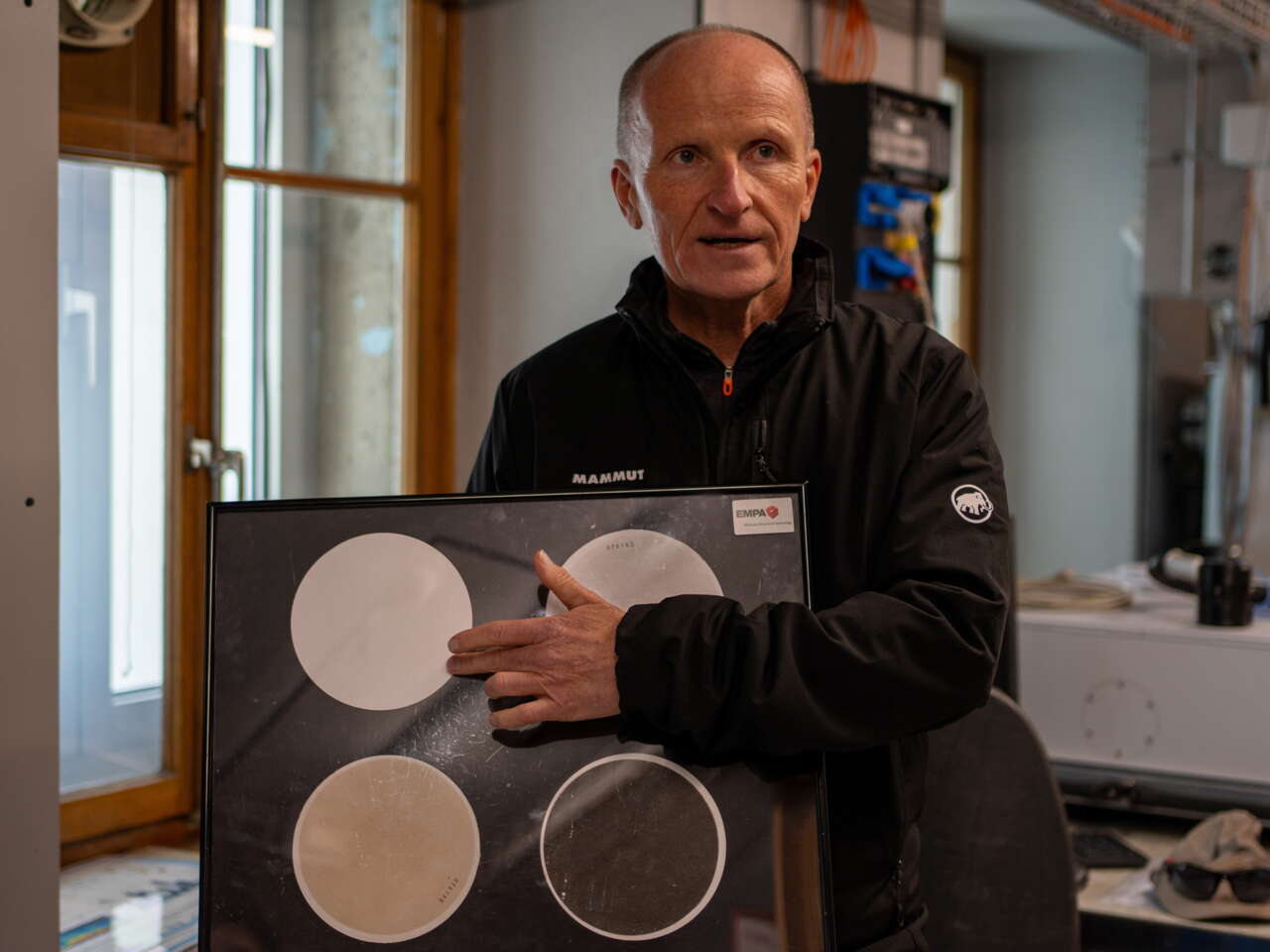

The air is good in Bern, but...

The Sphinx Observatory contains two other large laboratories, a weather observation station, a workshop, two terraces for scientific experiments and an astronomical and a meteorological dome. A fully automated federal particulate matter measuring station is also located here. Thomas Furter changes the filters every fortnight - and sends them in for more precise analysis. We find out: Even if the air in Bern is generally good, the comparison with the air on the Jungfraujoch is striking. Or a filter is worth a thousand words.

Measuring devices, measuring devices and even more measuring devices can be found in another room of the Sphinx. Cables, plugs, screens - the volume of data recorded here is enormous. "Everything is automated," says Thomas Furter. Researchers visit periodically to carry out maintenance and repair work. "I can also fix minor faults myself."

A special kind of refrigerator

My stomach makes itself known. Luckily it's lunchtime. We head back to the research building, the home of Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter. Both of the maintenance couple have their own bedroom on different floors. The living room and kitchen are shared. There is a fitness bike in the parlour. "Sonja uses it regularly," we learn from Thomas Furter. The "fridge extension", as they call the opening to the gallery, is special. It's cold enough here all year round. The shopkeepers order food from the Coop Wengen by email. This is a service offered by the shop. They are delivered by the Jungfrau railways. Did you know? The Jungfraujoch has its own postcode, 3801. "When we order something, people sometimes ask about the delivery address," says Sonja Stöckli - and laughs. But back to the reason why we're here. Lunch. Stöckli/Furter usually only cooks in the evening. "We usually just have bread and cheese for lunch." Today is no exception. We give the couple a well-earned break. Not least because our hunger doesn't diminish as we watch them eat. We also fortify ourselves - in the midst of the tourists, what a change of scene. Afterwards, we become tourists ourselves for a short while - we make a detour to the ice palace and the plateau. And we realise that the fog is lifting.

From cirrocumulus to stratocumulus

We can't see as far as Alsace yet, but it's definitely worth joining the "Wättere" again in the afternoon. "Visibility about 15 kilometres," says Sonja Stöckli. "7/8 cloudy, fog, snow-covered, with wet snow," says Thomas Furter. His partner nods in agreement and adds: "Altocumulus clouds at around 3700 metres, cirrocumulus clouds at 7000 metres. They are very rare." Thomas Furter also discovers stratocumulus clouds, "but not from a thundercloud". The two sound like meteorological professionals.

Incidentally, they have also made friends on the roof of the Sphinx - feathered friends. The alpine choughs are always happy to have a little snack - and have no fear of contact.

Back inside the Sphinx, Sonja Stöckli neatly enters what she has observed into the tablet. If she is unsure, she or Thomas Furter can use the binoculars for help.

Alone for two

"The location in the middle of the mountains, the view, the variety, the interesting people we meet. Simply a unique place to work," say Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter in unison. And an equally unique place to live. "But," says the eastern Swiss, "we also have to make sacrifices. Going to a restaurant in the evening, to the cinema, meeting friends - that's not possible." The couple socialise during their days off in the valley, in their second home in Flawil. And: "You have to like the solitude. "After closing time or when the railway doesn't run because of bad weather, we really are all alone." Alone for two. Actually, three of us. One Jungfrau railways employee stays on the mountain at night.

We make our way home. At 6.15 pm, the last tourists leave the Jungfraujoch. Shortly afterwards - in the so-called staff link - all those who have been doing their daily work today at 3454 metres above sea level. Almost all of them. Sonja Stöckli and Thomas Furter stay behind.

More information

Jungfraubahnen

Contact

Rail Info Interlaken

Höheweg 35

3800 Interlaken

Tel. +41 33 828 72 33

info@jungfrau.ch