History

"Oh look, look," cried Heidi in great excitement, "all of a sudden they're turning rose-red! Look at the one with the snow and the one with the high, pointy rocks! What are they called, Peter?" "They're not called mountains," he replied (from Johanna Spyri, Heidi's Years of Learning and Travelling). We are a little surprised at the goatherd's answer. The mountains do get names. In Peter's time, however, the white peaks had no economic value or use. That's why they weren't baptised.

Large rivers, settlements and valleys were baptised first - then it was finally time: our high alpine peaks were given their names.

In earlier centuries, the peaks were regarded as barely accessible terrain of no economic importance. Of course, farmers couldn't graze cows on the Eiger either. So the population had absolutely no need to name them - except, of course, when the peaks served as reference points for spatial orientation.

The word "mountain" was used for alpine terrain and pass crossings - but hardly for summits.

Many of today's mountain names date back several centuries. However, they did not always refer to the same peak, as the example of the Mönch shows. The name first had to be officially established, until then a peak could go through several name changes.

The flourishing Alpine tourism brought constancy: the continuous naming of the peaks. The Alps were discovered as a tourist destination from the Renaissance period onwards. However, the first ascents of the high Alpine peaks did not date from before the 19th century.

Nine

Four-thousand-metre peaks tower high in the Bernese Alps. But only two of the triumvirate are included.

Now let's talk about the triumvirate.

For the sake of completeness, we list the nine four-thousand-metre peaks in the Bernese Alps here: Finsteraarhorn, Aletschhorn, Jungfrau, Mönch, Schreckhorn, Grosses Fiescherhorn, Grosses Grünhorn, Lauteraarhorn and Hinteres Fiescherhorn.

First of all, the origin - let's trust the legend

Wengernalp was once inhabited by a family of cruel giants. They were known far and wide for their evil disposition. One day an old, poor man with worn-out clothes came along and asked the giants for a drink of milk. The giants, however, refused him and told him that he deserved nothing but water.

Ohaa, if that ends well. We can already see the disaster coming.

The Wengernalp Railway poses in front of the Wetterhorn. Fortunately, there are no more ferocious giants to be found here these days.

What do you think became of the evil giants?

We are right, of course. The disaster came: The old man insulted the giants and they wanted to get their hands on him. Of course, a giant wouldn't be afraid of such a wretch. But nobody knew that the old man was a mountain spirit and therefore much stronger than all the others. Well, tough luck. The giants really couldn't have expected that. The mountain spirit cursed them for this evil deed. As a result, they suddenly began to grow. They grew bigger and bigger and became solid rock and ice. So the father became the Eiger, the sons the White and Black Monks and the daughter the Virgin. Makes sense. That's probably how it was.

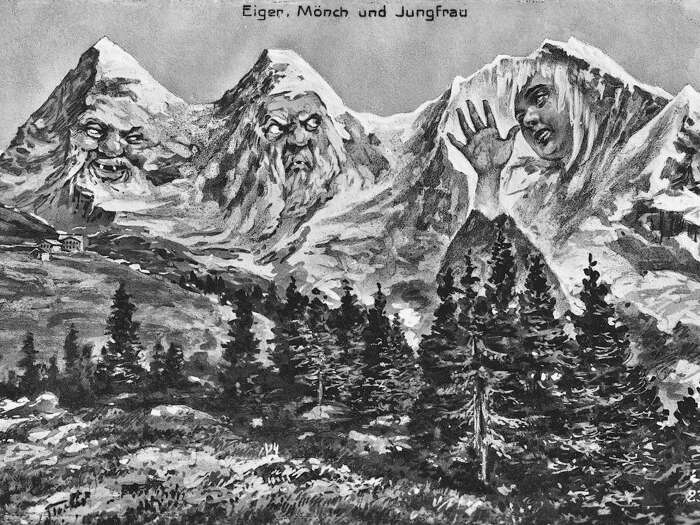

Father, sons and daughter united in a solid rock. They have offended the wrong man.

There they are - the giants turned to rock.

Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau - the order is just right. It has become engraved in our collective memory. We would never reverse the order. It fits like this.

The man-eating giant lives up to his name

The Eiger is one of the first Swiss high peaks to be mentioned in documents. As early as 1252, the words "ad montem qui nominatur Egere" in the first document may refer to an alp, whose name was later transferred to the summit. We don't know for sure. However, it was half a century before the Eiger was first mentioned in German - with the words "under Eigere".

It is said to be an ogre, a man-eating giant - at least according to the popular interpretation of the name Eiger. Of course, we immediately think of the likeable Shrek with his donkey. Unlike Shrek, however, the Eiger has a fearsome reputation. The north face of the Eiger makes sure of this in an impressive way.

Many roads lead to Rome - or to the meaning of the name Eiger.

The first settler below the Eiger is said to have had an Old High German name: Egiger or Agiger. The mountain above his pastures was therefore called "Aigers Geissberg". Of course, that could have been the case. Or does the Latin tell us the correct meaning? The Latin word "acer" developed into the French word "aigu". Both words mean "sharp" or "pointed". Here, of course, reference is made to the shape of the Eiger. The third explanation also judges the Eiger by its appearance: The formerly common spelling "Heiger" may have developed from the dialect expression "dr hej Ger" ("hej" means "high" and "Ger" was a Germanic throwing spear). Well, one, two or three? We don't know.

A popular story tells that our "Ogre Eiger" constantly wants to lay his lustful paws on the virgin. But he is constantly prevented from doing so by the monk. Poor ogre... or poor virgin?

There is so much confusion and uncertainty about the naming of hardly any other peak.

Sandwiched between the Eiger (3970 metres above sea level) with its spectacular north face and the Jungfrau (4158 metres above sea level) with its pretty appearance, the Mönch has long led a wallflower existence.

This starts with its name. It didn't even have one for a long time. Until well into the 19th century, it was called Eigers Schneeberg, Hinterer Eiger, Kleiner Eiger or Inner Eiger. It later became the Weissmönch, Grossen Münch or Gross-Mönch.

It is probably most obvious that the name derives from the monks in the monastery nearby. But no, unfortunately not. Instead, there were alpine pastures at the foot of the monk, where geldings, known as "Münche", were once summered. This is why the mountain above the Munich Alps was called "Münchenberg" and eventually Münch and Mönch.

But not only has it borne many names, it has also had to be measured several times. And for the sake of surprise, always with a different result: the figures varied from a minimum of 3976 to a maximum of 4114 metres above sea level. Today, it is undisputedly one of Switzerland's 48 four-thousand-metre peaks.

4107

metres above sea level is the official height of the Mönch. It was difficult to determine the height, as the Mönch has a crest of firn that has grown in recent years.

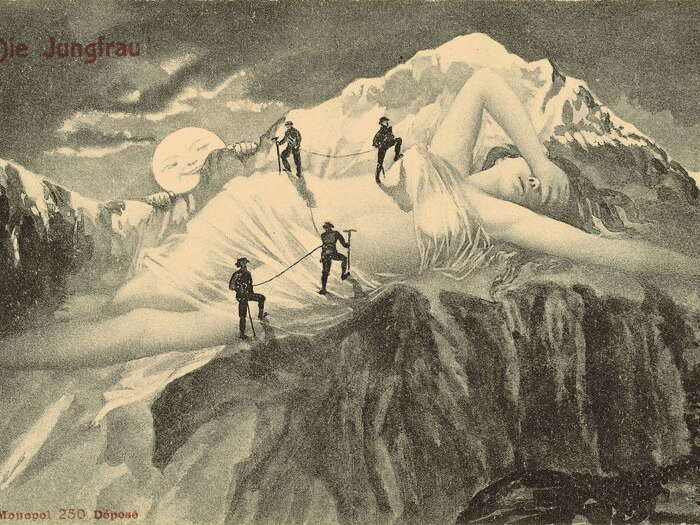

We can only speculate about the derivation of the name of the third peak in the triumvirate. With a few, very rare exceptions, this peak has borne its current name for centuries.

In the 14th century, there were many Premonstratensian double monasteries such as here in Interlaken - an order founded according to the Augustinian rule.

The cloak, hat and beret worn by the monks and choir virgins were pure white. We are happy to assume that the monks in Interlaken had the idea of comparing the shimmering white summit with a Premonstratensian choir maiden.

The supposed inaccessibility of the mountain peak certainly contributed significantly to this.

The name Jungfrau certainly first appeared in 1577 in Thomas Schöpf's "Chorographia ditionis Bernensis". In this work, the author made the definite statement that the Jungfrau was a mountain covered in eternal snow and ice and therefore completely inaccessible, and that the inhabitants therefore derived the name from an untouched virgin, as it were.

The name would then probably have been transferred from a Jungfrauenalp to the summit above.

The Jungfrau railways make it possible.

Thanks to the Jungfrau Railway, we can travel smoothly through the Eiger and Mönch all the way to the Jungfraujoch-Top of Europe - and all in the comfort of our seats. In keeping with its name, the Jungfrau remains inaccessible. At least by train.

At the end of the day, it doesn't matter whether the three peaks owe their names to monks, geldings, choir maidens or ancient Germanic names - we all agree on one thing: the triumvirate simply looks cool.

More information

Jungfraujoch- Top of Europe

More information

Schilthorn-Piz Gloria

More information

Photos: Jungfrau Region, Jungfraubahnen

Story: André Wellig

Autumn 2017

Contact

Jungfrau Region Tourismus AG

Kammistrasse 13

CH-3800 Interlaken

Tel. +41 33 521 43 43

info@jungfrauregion.swiss

![]()